Olympic Gold: Harrison Dillard and Military Athletes

From the chaos of war to the triumph of the Olympic Games, Harrison Dillard’s story embodies courage, perseverance, and excellence. A veteran of the U.S. Army’s segregated 92nd Infantry Division, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, Dillard returned from WWII to become one of America’s greatest athletes.

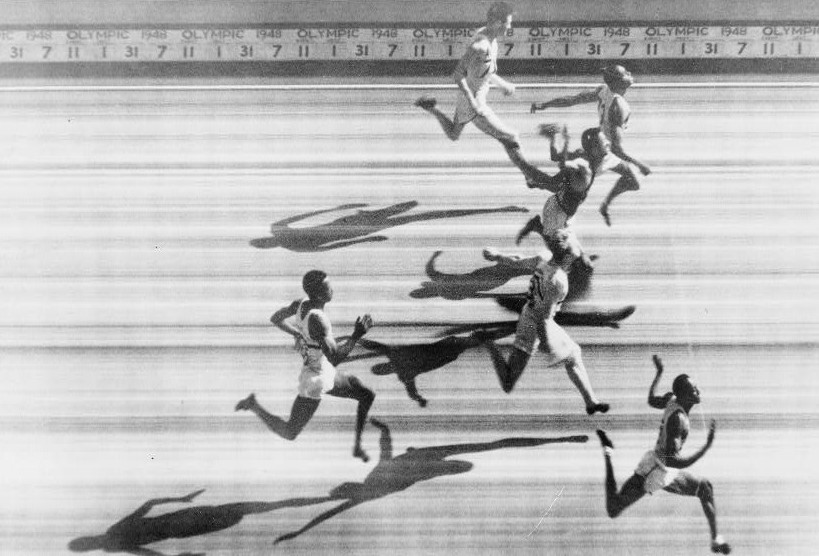

London, summer 1948. All eyes were on the first Olympic Games held since 1936. After years of war, countries from around the world met not on the battlefield, but on the track, in the swimming pool, and inside the boxing ring. At Wembley Stadium, six sprinters crouched on the track for the finals of the 100-meter dash. The gun sounded, and in just 10.3 seconds, it was over. The race was so close that a photograph was used to declare the winner.

The image was striking — six of the world’s fastest men caught seemingly in mid-flight, none of their feet touching the ground. They were frozen in a furious burst of speed, out-running their own shadows. The photo made it clear: William Harrison Dillard, at the bottom of the image, had won gold and earned the title of “the fastest man alive.” His arms and hands flung upward, his right leg bent backward, the toes pointing toward the sky — a moment of pure triumph captured forever.

Dillard’s victory was even more remarkable considering his journey. Just three years earlier, he had not been sprinting on a track but dodging mortar fire in Italy as part of the 92nd Infantry Division. “I was extremely proud of being a Buffalo Soldier,” he said in a 2008 interview with the Library of Congress Veterans History Project.

As the 2021 Olympics approached, it was worth remembering that Dillard — alongside Charley Paddock and Mal Whitfield — stood among the armed services’ greatest Olympic champions. The Department of Defense lists 19 members of the armed services participating in that year’s Olympics, a testament to the long history of athletes who also served.

Paddock, who served in the U.S. Army Field Artillery during World War I, won two golds and two silvers in the 1920 and 1924 Olympics. He returned to service in World War II and was killed in a 1943 plane crash in Alaska. Whitfield, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, and Dillard together won nine Olympic medals — seven of them gold. Four belonged to Dillard, five to Whitfield, and all three men are enshrined in the U.S. Olympics & Paralympics Hall of Fame.

Dillard’s 1948 Olympic journey didn’t begin smoothly. He failed to qualify for the finals in his signature event, the hurdles, even though he was the world record-holder. After hitting several hurdles, he barely qualified for the 100 meters final and was placed in the far outside lane. Yet, against all odds, he triumphed.

Perhaps most inspiring of all, Dillard had attended the same high school in Cleveland, Ohio, as Jesse Owens. Owens had famously won four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, humiliating Adolf Hitler’s notion of Aryan supremacy. A young Dillard had watched Owens run as a high school senior and vowed to follow in his footsteps.

With the 1940 and 1944 Olympics cancelled due to World War II, the 1948 Games marked the first since Owens’ triumph. And so, in poetic symmetry, two men from East Technical High School — a decade apart — were crowned the fastest men on Earth in consecutive Olympic Games.